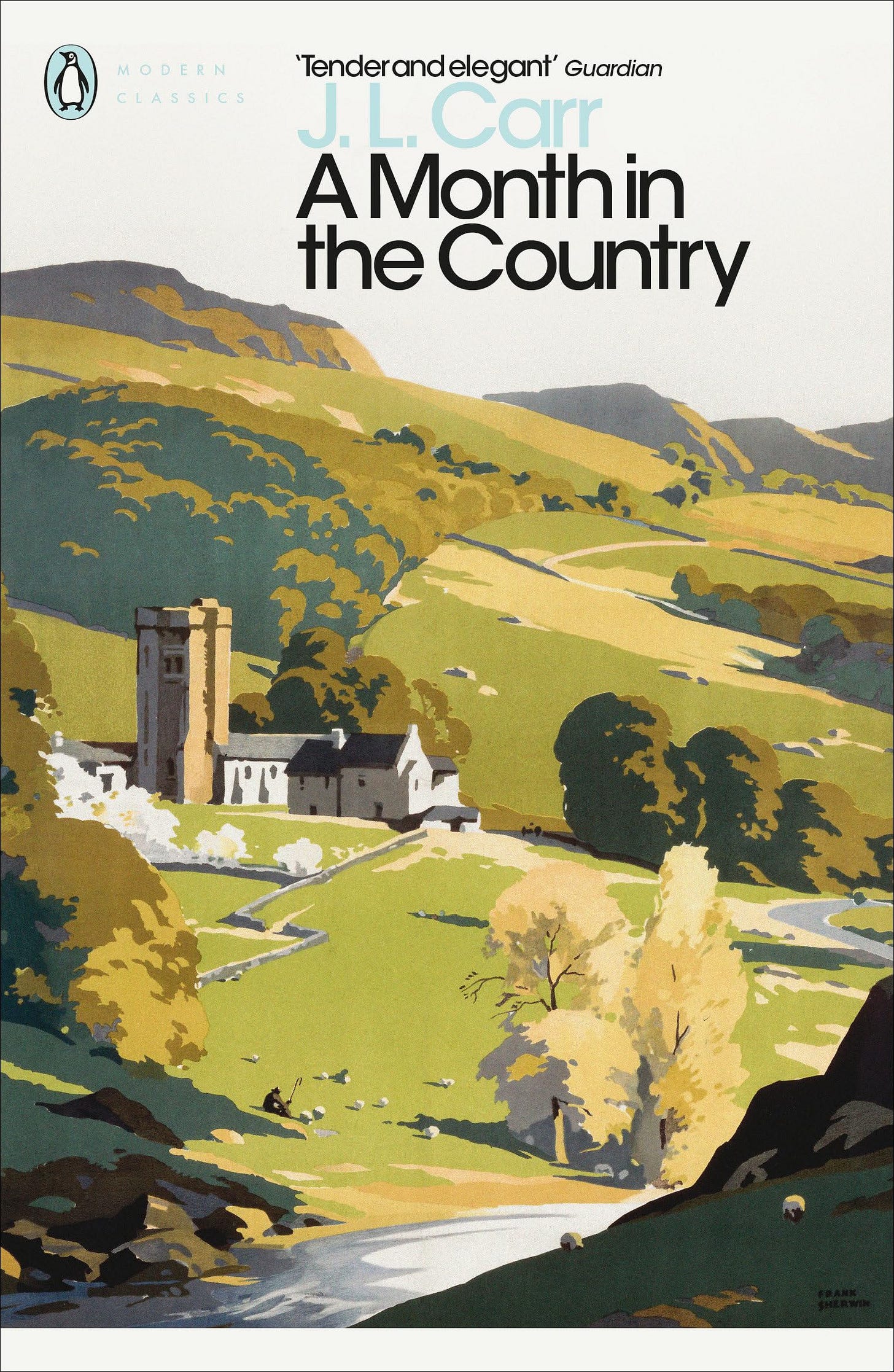

One of the great novellas of the English summer is J.L. Carr’s A Month in the Country. It’s set in the period just after WW1 when England was trying to revive itself, and hadn’t yet realised that the wounds of the Great War were effectively mortal ones. The 1980s, when the novel was published, seem to have seen a fillip of interest in the period either side of WW1 as it related to England. The novel was also made into a good, if rather gentle, film in the vein of a Merchant Ivory production which stars early career Kenneth Branagh and Colin Firth.

The main character, Birkin, is a man who’d served in France and suffered greatly for it. His work as an art restorer, and his time spent in the fictional Yorkshire village of Oxgodby. As he settles into the village and progresses through the restoration of the Church’s medieval “Judgement” wall painting, the psychic scars of his time in the war slowly heal and he his more obvious shell shock symptoms subside.

Like another great English summer novel of the inter-war period, Brideshead Revisited, it’s also about religion. Rather than Waugh’s angle on grace, Carr instead looks at various different religious beliefs and their social impacts.

The painting Birkin is restoring is one that is believed to have been covered up during the reformation. It would be difficult for anyone to point exactly when, as the reformation (and iconoclasm) went through multiple phases and were never exactly welcomed in the north of England. Through restoring the painting, working in the footsteps and brushstrokes of its creator and experiencing its symbolism Birkin develops an understanding of the medieval Christian worldview - Catholic, at a time when in western Europe that just meant universal.

The reverend JG Keach is another key character, and represents the established church - the Church of England. He does not appreciate the medieval art, and views it as something of a distraction. He never goes deeply into any theology, but does generally offer a staid, slightly pretentious, and slightly higher social class view of the situation. He laments that the village has little need of him in religious terms, simply using his services to mark the comings, joinings, and goings of life. The reverend and his wife inhabit a rectory which is vastly oversized for their needs and which serves to remind us that as much as Keach is proud of the institution he serves, he is also trapped by it. His wife is written to provide the soft edge where he is hard, and the warmth and happiness where he is cold and aloof. One gets the feeling that Carr respected the Anglican church, but did not like it overly much.

The next most obvious religious angle is that of the non-conformist station master and his family. They are a “Chapel” family, usually taken to mean Methodist. Methodism was a very popular branch of Christianity in England, and over time worked to fit in with the prevailing hierarchy of the country - Methodist Central Hall has a cathedral like silhouette and faces Westminster Abbey in London. Throughout the north of England, Methodism spread along railway lines and through coal fields. The distinctive simple and low façade of a Methodist church is present in nearly every village I go through here. The family, and their beliefs, are generally coded as being welcoming, authentic, and genuine if not a little too earnest and of a notably more working class tone than the Anglicans.

The final group is that of the outsiders, men who have placed themselves outside Christianity. Birkin’s restoration of the painting is mirrored by an archaeologist, Moon, who is seeking to uncover the grave of medieval squire of the village. Notably, Moon works outside church grounds and is more comfortable below ground than above it. As the novel reaches its conclusion we find that Moon was in military prison for the last 6 months of the war, for having an illegal relationship with his batman. It’s never quite obvious if it is the sexuality, the taboo, the lack of self restraint or the punishment causing him to abandon his men that leaves Moon outside religion.

Ultimately, Moon’s archaeological search is fruitful and he discovers the grave of the long dead squire. In a poetic turn we find that this squire too was outside the Christian church as he appeared to have converted to Islam during the crusades and this is why he was buried outside hallowed grounds. Carr treats the outsiders with a great deal of empathy, and never suggests a path towards, or indeed a need for, their redemption.

The novella is both short and finely crafted, and the film holds up well even if the picture quality is rather poor. It is also noteworthy for having an excellent soundtrack by Howard Blake which captures the mood, time and place perfectly.

This post intrigued me, so this afternoon I took time to watch the film version. The plot is simple enough and the characters easy to understand from the start. It also involved some of my personal interests: art history, old graves, English history, northern accents, and organ music. How could I not love this?

The film's respect for the source material seems quaint in the current day. I could not help thinking that, if this were made today, Birkin would either be making love to Mrs. Keach in the belfry, or he would assume the role of Moon's erstwhile batman in the tent. 1987 was a better time, and shame on me for worrying about the direction that the story might take.

I should like to seek out more period pieces from the 1980s.