The Medieval Mindset and Tradition

An examination of what the pre-modern mind might have been like, and why there's no going back.

Calls to return to some prior, more virtuous state are a pretty commonplace occurrence, and there’s also the attraction of a “return to tradition”. What I shall explore here is some aspects of what that pre-modern mindset might actually have looked at, why we can’t go back to it, and why going forward and forging something new is important.

Place

I don’t mean this in the sense that people didn’t travel as widely as now. We know that military service, trade and pilgrimages took people hundreds of miles and at a pace and level of difficulty that dwarf modern travel.

By place, I mean that everyone in the medieval world had their role and place, and only true outsiders didn’t. Outsiders in this period were literally outside the law, so had little protection from law or society. It’s why exile existed as a punishment - what would only be an inconvenience today was something that removed social protection and status then.

Having a place and role ordained for everyone had the benefit that everyone had something to do, and nobody had to spend years (or decades) wasting their life trying to choose. I often wonder how much choice people really want when a theme I often return to in my fiction writing is that many people really do wish that someone else could tell them what to do or make decisions for them.

This system certainly has it’s negatives, but then consider that most generation Y and Z will be worse off, have less stability and lower relative wages than their parents. Add in the fact that social mobility is a myth for most people and you see how we’re slowly heading back to a negative version of this for forty-nine in every fifty people.

Wealth

Wealth’s a funny thing, and when you start to try to separate the idea from money it becomes even more so. That’s part of the design of the modern world. There’s a reason why you come across lots of references to income in 18th and 19th century novels - it was tied to land and agricultural rents. Wealth only became divorced from place and the place’s people through the industrial revolution. This has the effect of forcing the wealthy to think over a longer term - they can’t just exploit a situation and run because their wealth is a place, not a box of fungible tokens which are as useful anywhere they care to go.

Of course, monetary economies are great at driving people out of subsistence situations and into the lowest of possible jobs. From the Scottish highlands to the Amazon tribes, the same phenomenon happens everywhere - join the money economy and be poor. Our medieval mind doesn’t have that option; some are poorer and some are richer but those roles are largely fixed. Only huge population changes and agricultural disasters really changed those roles, there was no way of forcing people into new and cheaper roles or importing a new class of people to undercut those already there.

Benevolence

One constant you see in rebellions, from Wat Tyler up until the Russian revolutions of 1917, is a focus on eradicating “bad councillors”. Rarely was any great anger directed at the ruler himself, but usually at those around him and trying to steer his policies. Although some of this effect is politic or religious, there was a greater sense that the man at the top was ruling to the best of his ability and with a general sense of benevolence. Of course, there were awful kings and queens but in general the populace seemed to feel that rulers intended to rule for the good of the kingdom. Modern political rule is guided by different concepts - economics, liberalism, nationalism, progressivism or globalism for example. The simple concept of benevolent rule has long passed.

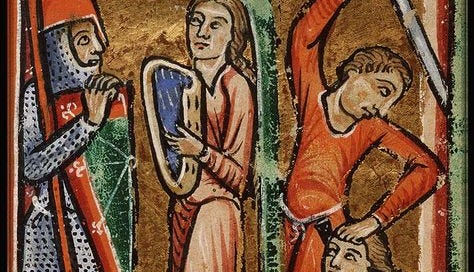

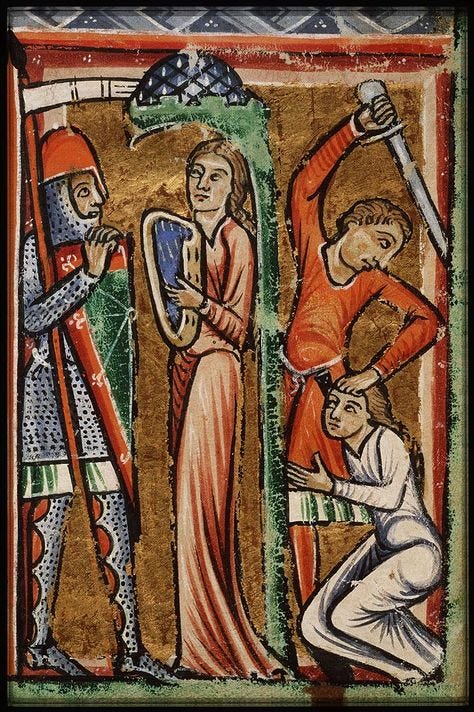

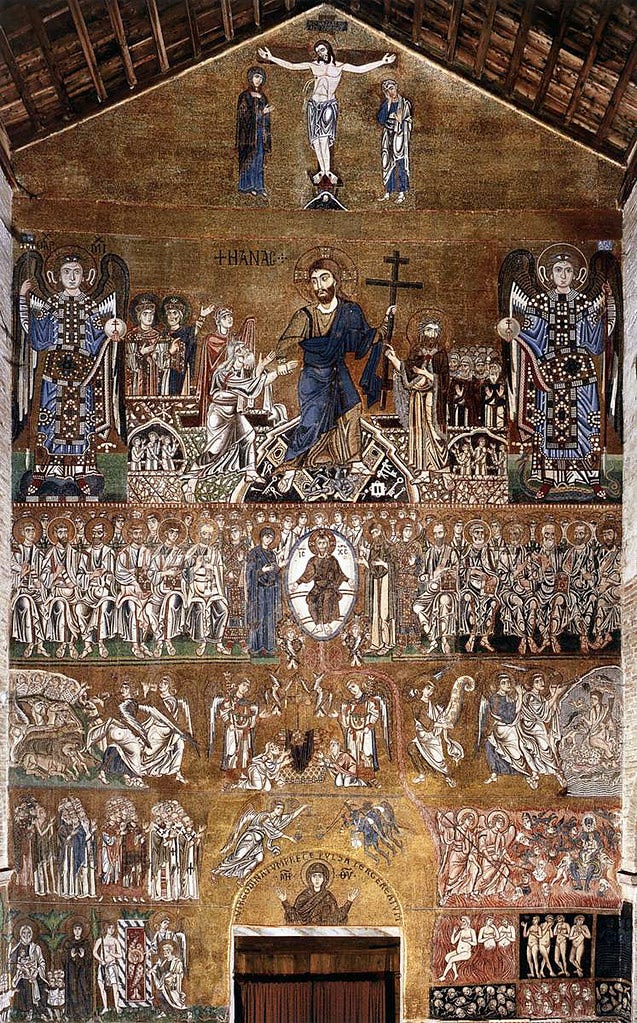

Order

Following on from benevolence and place, we find the medieval concept of order. Our forebears in the middle ages knew that the system and world they lived in had been ordained in a set way by god. There wasn’t really anywhere as much resistance to this idea as modern people might expect. Progress wasn’t really part of the pre-modern mindset. God created things this way, they’d always been this way and always would be. You can see this demonstrated in the medieval dress of bible characters in art from the period.

It’s also why the reformation was met with popular revolt and war in Germany and England - it literally broke the world and forcibly introduced a totally different and individual centred world view into what had previously been a stable and comprehensible system.

Teleology

Essentially the idea that things exist for a certain end or purpose, the pre-modern mind was far more teleological than ours, especially regarding people. Once everyone in society has a place and role, the next step is for them to have an ideal or perfect template to work towards. There’s an ideal for kings and priests. Chaucer’s true and perfect knight, a “veray parfit gentil knight” in middle English, gives a martial example whilst the most widely read book of the era was Thomas a Kempis’ “Imitation of Christ”. Everyone had a fairly clear ideal of what the perfect version they ought strive towards. There was no personal perspective in this, no relativism or choice. There was certainly discussion about these archetypes and they weren’t designed as achievable targets, but an inspiration.

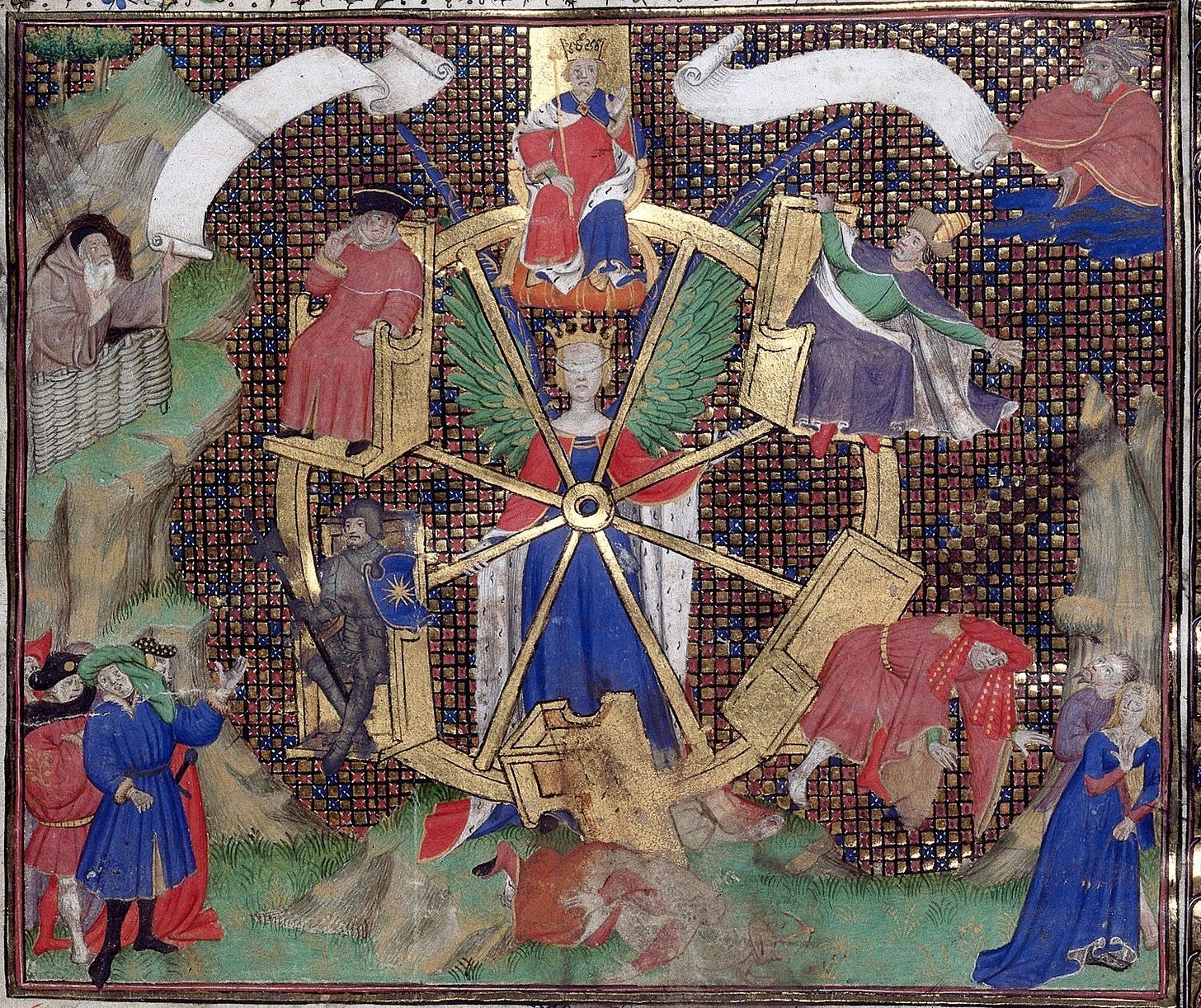

Wheel of Fate

The pre-modern mind often viewed the world through the concept of the wheel of fate. Men’s lives could rise, and even relatively ordinary and common men could achieve quite high status. However, these rises were often followed by a fall which frequently cost everything. Not like a modern politician, who spends 3 months in a country-club jail and then returns to his mansions and millions. When men fell from grace in this period they lost livelihood, status, home and frequently their life. Modern men can’t believe in such a wheel, although we may see rises we never really see corresponding falls. There’s certainly no faith that the wheel of fate still turns.

Values

When we can be fairly sure that people’s values so long ago were very different to ours. I can read history books written by left wing activist professors in the 1960s which are criticised as being hopelessly right wing by modern readers. The personal values of the pre-modern mindset are easy to guess at and quite divorced from ours. There was no doubt a greater belief in punishment than justice, Oikophilia nor oikophobia, a sense that deviating from convention was to condemned not celebrated and a general acceptance that this was their world. One would imagine that every value they held was alien to our modern values and vice versa.

Now What?

Having looked over what a pre-modern mindset may have looked like we can see just how different some of it truly was. There’s no going back to that, not even in a handful of lifetimes. That world of order is gone from us. Every exhortation to return to tradition is futile, and the only thing to do is to create something better anew. It’s one reason why political conservatism seems pretty much defunct as an ideology now - simply asking what it has conserved reveals how hollow it really is.

Soon We’ll look at the competing modern mindsets.

In the medieval period, the apprentice would learn from the master, and in time, could move and start his own business, or could take over the master's business.

They could own part of the business, which employee today can't.

Excellent!!