Force to Space, Speed to Range: The Great War Part IV

A look at why the tactics of the First World War were bloody, why they weren't anywhere near as poor as commonly thought of, and the reasons for that.

The common belief about WW1 very much follows the “Lions led by donkeys” narrative that sees the period as the very nadir of generalship and tactics. As good as Blackadder was, the series certainly perpetuated this viewpoint.

To understand the tactical problem of WW1, a look at numbers is essential.

One of the British Empire forces’ most common heavy artillery pieces was the BL 6-inch Mk VII naval gun. It could fire 8 rounds per minute, at a range of up to 12500 metres (13700yds) and with each shell weighing 45 kilogrammes (100lbs). At the same time, infantry forces were still largely dependent on advancing on foot. They certainly had train lines running up to, and parallel with the front line but that’s useful for defending, supplying and massing troops. It doesn’t help with advancing at all. There was also use of London buses to move troops around - 24 men and their equipment could be carried at a normal speed of 26km/h (16mph).

This means that the crux of the tactical problem was that even if the enemy directly opposite your line was utterly eliminated, the maximum speed you could advance was basically no different to soldiers 2000 years earlier. However rather than dealing with archery or open sights artillery firing a couple of hundred yards, and advance had to come under the fire of gigantic exploding shrapnel shells from a highly accurate artillery piece with an effective range just shy of 8 miles.

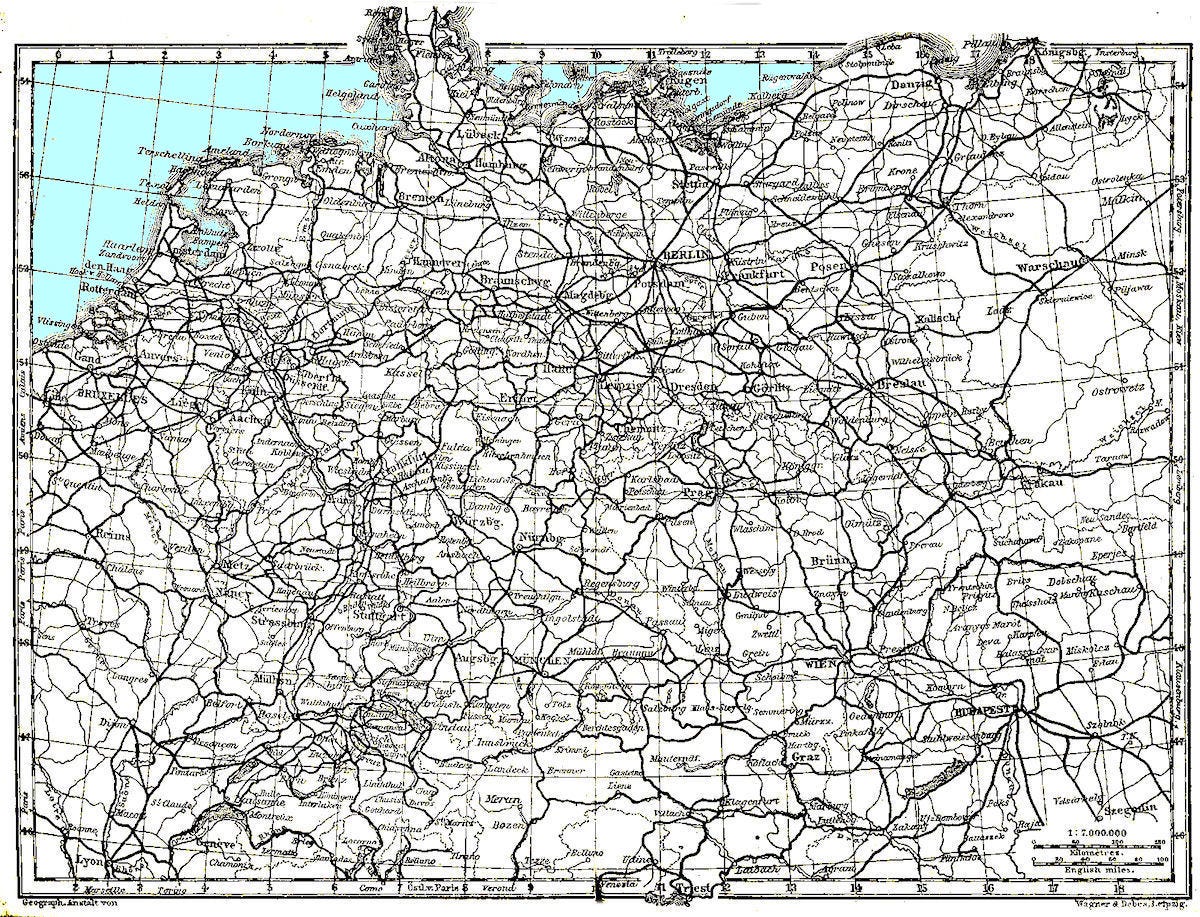

The numbers mentioned above also serve to illustrate the reason why warfare of this era was a battle of rail lines and railheads - a single artillery piece could fire over 40 tons of ammunition in an hour. Although I doubt continuous fire was kept up this long, but this serves to illustrate the logistical demands. A constant supply of railway carriages and horse-drawn carriages would be needed to keep the artillery supplied. The horse drawn carts were likely more use closer to the front, where smaller calibre field artillery dominated.

At the same time as all of this, your offense is fighting through mud and enemy support trenches, the enemy’s interior lines of roads and railways can keep their artillery supplied with shells and shuttle good numbers of troops where they are needed.

Ironically for such a technological war, this is why there was still a reliance on cavalry to try to exploit any breakthrough. Whilst the mounted lancer might seem like a relic of an earlier age, cavalry were by far the fastest units available to generals and therefore the logical choice for exploiting any gaps. their speed meant they were under artillery fire for a shorter time, harder to range in on and could perhaps get into a good position before defensive reinforcements came. Of course, the downside is that horses are pretty big targets compared to men. Some of the biggest advances in the horrifically costly British offensives of 1916 were made by mounted units, such as the 20th Deccan Horse, an Indian cavalry unit.

To summarise, the first part of out tactical problem is that weaponry outranged movement so greatly that any successful attack would remain under heavy fire for hours and had very limited prospects of actually punching cleanly though a defensive line or being reinforced in a timely manner.

The second element of the problem is the ratio of force to space. To put this simply, more men in a space makes for more defensive and costly warfare. This is one reason why eastern European battles from the renaissance onwards keep higher proportions of cavalry - the lower density of soldiers in a space puts a higher premium on manoeuvre. The difference in style between the warfare in the Western and Eastern theatres of the American civil war also illustrate this point - a great ratio of men to space results in bloody trench warfare. The battles of WW1 follow this too, with much greater movement and possibility for victorious attacks being possible on the more sparsely defended eastern front.

The sheer number of men in place, the giant an overlapping range of artillery pieces, the slow movement of troops, the need for thousands of tons of supplies all served to make a successful attack very unlikely.

This was compounded by the technological issues of communications. The British army relied on telegraph and telephone communications - both dependent on long and fragile wires. Although these systems were effective, they were better suited to prepared defences. Indeed, the communication back from any successful breakthrough would only come back to friendly lines as fast as the man running with the message in his hand.

Despite all of these problems, British and German forces did eventually develop the more flexible and independent small unit tactics which would be effective in 1918 and throughout the second world war. As much as the generals of 1914-18 have been portrayed as mindless butchers, they really did have the deck stacked against them and no-one, no-matter how much of a tactical genius1 they may have been, could realistically have done any better. It’s interesting that the speed of movement, improvement in communications and reduction in numbers that WW2 saw lead to a more dynamic style of warfare.

I think Brusilov was perhaps the only army level genius of WW1, and even then his greatest achievement may have been to avoid the Germans and pick on the Austrians