The Modern Mindsets. Part 1: Openness

Following on from the medieval mindset, we look at the modern world and the first of its two alternatives; Openness.

Having previously looked at the pre-modern, medieval mindset, it’s time to move on and look at the two main competing worldviews of the modern era. They don’t date precisely from the start of modernity, indeed it seems to have taken until the mid 19th century to see both viewpoints become clearly defined. Their traces can be detected in earlier periods, like the English civil wars and the French revolution. For our purposes though, the two opposing modern world views are best encapsulated by thinkers and visionaries from between 1850 and 1914. Note that these are mindsets, worldviews, the fundamental groundwork which underpins the way people think and act. To misquote, politics is very much downstream of world view.

This is not meant to be a thorough examination of all 19th and 20th century philosophical thought, simply a look at what I believe are the two opposing currents of it.

Fifth century Athens is widely seen as a particular Golden Age in which the foundations of the Western World were shaken, improved and rebuilt. The ideas, literature, philosophy and art of the period is still influential, and all this came from a small city state at the centre of a province where no more than 400,000 souls lived.

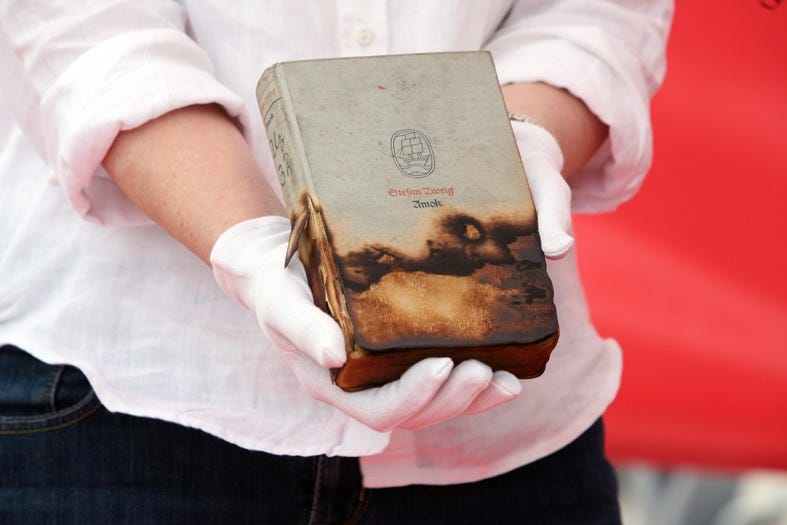

Late 19th and early 20th century Vienna was just as influential, for its café culture spawned many of the leaders and thinkers whose lives influenced the whole trajectory of the twentieth century, and are still influencing us today. There was a point where Tito, Hitler, Freud, Trotsky and Stalin were all living in the same quarter of the city. Stefan Zweig tries to capture the feeling of the place in his famous book, the World of Yesterday. Whilst the book is certainly well loved it didn’t move me at all. Rather than harking back to a golden era, Zweig mostly name drops and fawns over other writers who deigned to notice him.

His book is mainly interesting to me because it hints at something repeatedly through the passages on the pre-war era. Zweig frequently equates happiness with freedom from rules, sexual morality, questions of nationality and indeed even the need to earn a living. Some of this comes from his wealthy background, which also spared him the ravages of the first world war. There’s also a feeling that the multi-ethnic and multi-lingual Hapsburg empire might have given him a belief in how these human divisions could be overcome, even if the latter part of the emperor Franz Josef’s can hardly be taken as an example of peaceable stability and freedom.

However, perhaps the largest part of this love of openness seems to be related to the Viennese vogue for Freud. Zweig states that Freudian psychoanalysis was a prime reason for the difference in relations between the sexes, and summarises his understanding as being;

Easy for us, who since the time of Freud know that whoever seeks to supress the consciousness of natural desires not only fails to remove them but dangerously displaces them into the subconscious

This effectively outlines the credo of the “Openness” world view, that social limitations and man-made laws are a dangerous negative, and that the goal of society should be removing these barriers and impediments and allowing people to act on their natural desires.

We can see this “Openness” throughout the modern world, where the level of enlightenment or quality of a state or society is measured by what its population has been made free from or free to do. It’s a very pervasive view, and one which surrounds us so completely that it’s difficult to even find a name or a clear expression of it. One can frequently come up against the defence that Openness is only criticised by those who are not “educated” enough to understand and value it.

This Openness side are the heirs of the Jacobins. The fruits from this tree and are responsible for progressivism the modern left, feminism and most of the social frameworks pushed in the last 30 years. The entire Openness stance reaches is highpoint in the work of Karl Popper during World War II, who makes sure to conflate freedom from restrictions with what is good;

“in the perennial and dangerous struggle for building a better and freer world”.

It should be noted that Popper is in favour of restricting who exactly freedoms should be allowed to, in order to prevent the rise of any of the enemies of Open society - in his time Fascism and Communism being the obvious candidates. Indeed, since 1945 Popper’s ideals have had something of the feeling of an orthodoxy throughout the west.

Zweig’s books were burned by the Nazi regime, he fled the continent to Britain, and then on to Brazil where he eventually felt driven to kill himself.

Who is this world-view of Openness for? There’s a thread, notable in Zweig’s book and perhaps best expressed by Popper;

“The wise man belongs to all countries, for the home of a great soul is the whole world.”

This gives us the sense that the true aristocracy of their world are the freest spirits, those not hemmed in by race, religion or nationality. Indeed, Zweig finds his greatest sense of personal freedom in Berlin, away from family and connections (but notably, not family money or a common language). The purpose of this elite is therefore to break down barriers; those that prevent people from expressing their desires and also those that compel them to do something they don’t desire. Zweig goes on to talk about a group of the most enlightened pan-European intellectuals who would create a freedom and an open society which all are intended to benefit from.

The Open Society is sill an idea which has much currency in our current times, and indeed is the name of one of the world’s largest and most active political foundations, now headed by Alexander Soros.

So what about the other side, is there a viewpoint which sees a good society as being something other than the one with the greatest freedoms? There is.

It is hard not to detect the foul stench of Rousseau in this openness business.

Good stuff this piece.

Liberty comes with responsibilities. Responsibilities to self, family, community, and state. It also comes with discipline, for without discipline, we are little better than animals.

When people are allowed to do "Whatever they want," they fall to self-destructive means. (Drug use, Sexual immorality, promiscuousness. lack of authority."

Modern man has lost that sense of place, of knowing where he belonged, what he had, and what he earned. When you get something for nothing, you treat it like trash.